Development of Monkey Bridges and Sustainable Monitoring Networks in the Burica Peninsula, Chiriquí, Panama

Oscar Thiercelin and Greig Hospes

McGill University

Host: Proyecto Primates Panamá

Host Contacts: Dr. Ariel Rodríguez-Vargas

Email: ProyectoPrimatesPanama@gmail.com

April 30th, 2020

Introduction

This research project took place along the Burica Peninsula, a small stretch of land in the lowland regions of Chiriquí, Panama. This area holds large ecological significance in that it is the last remaining habitat of the Mono Tití Chiricano (Saimiri oerstedii), a highly endangered species of monkey. The Mono Tití used to be spread over a much larger area of Panama, particularly across the Chiriquí province, but now occupies only this small peninsula in Panama’s southwest corner and a small area in Costa Rica. As well as the Tití, the region is also home to two other species of monkey: Mono Aullador (Alouatta palliata) and Mono Cariblanco (Cebus imitator) (Proyecto Primates Panamá, 2019), plus a large variety of other forms of wildlife. On top of the ecological significance of the region, there are also many communities that run down the length of this peninsula including Puerto Armuelles, Las Mellizas, Yerbazales, Caña Blanca, Limones, Bella Vista, and others. These villages are full of very kind and welcoming people that have formed an incredible sense of community in the area.

In the last year, the area has had the introduction of a new highway that connects the communities of the coast to the rest of Chiriquí. While this new road (Carretera PTP-Limones) seems to be a boon to the communities, allowing easier transport and increased connectivity with the surrounding areas, it may also have significant detrimental effects on the surrounding wildlife. Due to the nature of the highway it cuts straight through many areas previously covered with trees and vegetation. For this reason, the local habitats have been disturbed and fragmented which can be seriously harmful to the local species (Tigas et al., 2002; Haddad et al., 2015). The splitting of one habitat into many smaller habitats separated by a barrier – in this case the new highway – is a very straightforward example of habitat fragmentation (Boinski et al., 1998; Cuaron, 2000). In this particular instance, the fragmentation is especially dangerous to local wildlife populations because the presence of the new road brings cars that can strike and kill passing animals. During our discussions with members of the communities we found that approximately 15% of those interviewed had seen monkeys hit and killed by passing traffic within the last year since the road’s construction. This number only accounts for monkeys, and we are sure that there are many other species of animals harmed by the traffic and the new road. These anthropological effects in a habitat can have drastic changes on the ecosystem health and composition through processes such as trophic cascades or other large-scale ecological interactions (Silliman & Bertness, 2002).

After discussing with members of the community, we found that the people had much care for the wildlife of the area and topics such as conservation were very important to them. This response was larger than we had predicted, with approximately 95% of those interviewed stating that the conservation of the habitats around them was of serious concern. Unfortunately, even with such a positive response to conservation there appeared to be little to no action taking place within the communities. We believe that this is due to a lack of communication and organization, because when the community members were asked if they would be interested in participating in some form of group to aid in conservation initiatives we saw that about 75% of individuals were willing and even excited at the idea. These results were encouraging to us because they showed us that with time, communication, and organization, we will be able to do something meaningful with these communities.

In order to tackle the aforementioned issues and projects, we are working with Proyecto Primates Panama, an NGO based in Chiriquí, Panama whose primary goals are to promote sustainable development and conservation of biodiversity through environmental education and social empowerment. This group is run by Dr. Ariel Rodriguez-Vargas and Dra. Laura Patiño Cano, doctors in Biology and Organic Chemistry respectively. The organization was initiated in 2016 to begin their environmental conservation initiatives, working with help from researchers, students, and communities to further their goal of primate conservation, particularly in the lowland regions of Chiriquí (Proyecto Primates Panamá, 2019). The group is largely focussed on the study and conservation of primates and they do a great job of increasing community knowledge and involvement through workshops, education, monitoring tours, and other such actions.

Our initial work in the area gave us two goals to direct our work. The first of which is to combat the habitat fragmentation that has occurred in the area due to the implementation of the new highway. The introduction of corridors to allow animals to safely cross between fragmented habitats can be an effective strategy of lessening the negative effects of habitat isolation and fragmentation (Dobson et al. 1999). In the case of the Burica Peninsula, Proyecto Primates has begun to counteract this fragmentation through the creation of bridges between the treetops over the highway to allow monkeys (and other arboreal creatures) to safely cross without the chance of being struck by the cars and busses that frequent the area. As of now, the group has put five temporary bridges in place. Our work was to, through direct observation and discussion with members of the communities, analyze the use of these temporary bridges and the habits of the monkeys of the area in order to find which of the temporary bridges are the most effective and to find out where else along the highway new bridges would be most beneficial. As well, the plan is to convert the temporary bridges to more permanent structures so that this step forward against fragmentation will last.

Our next goal is to assist the communities in the creation of a sustainable ecological monitoring organization to aid in the efforts currently being run by Proyecto Primates. The idea is to bring the communities together on a topic that is important to them but that currently lacks organization. Due to the high level of interest in conservation topics within the communities we believe that the introduction of a monitoring network will both bring the communities together to a common goal as well as providing a sustainable flow of information for those working at Proyecto Primates. Unfortunately, due to extenuating circumstances we were not able to be in the community for the implementation of this network, but we have provided our host organization with the information necessary and a template for how to promote the creation of this organization. The hope is that once this network is up and running, the people of the communities will continue to contribute to the monitoring and conservation efforts on their own accord in order to provide Proyecto Primates with continuous, important information that will aid in both community cooperation and conservation initiatives.

Methods

As mentioned before, this project could be separated into two different sub-parts, nonetheless linked on multiple levels. The first part would be to create a map of Punta Burica and indicating where on the new highway new permanent bio-corridors could be built. In order to do so, we opted for a cross-sectional research design to gather new data. The second part is to create a sustainable monitoring network to permanently gather new information around the themes of the Punta Burica monkeys and global conservation. A participatory research design seemed logically suitable to conduct this part of the project.

The Map

The methodology chosen to create the most accurate map possible was to conduct a meta-analysis; to combine multiple sets of data gathered from various sources. We were able to go through with some of these sources but others had to be dropped because the research project was cut short. The first and main part of this exploratory research was to conduct a survey. This survey was designed to last around 15 mins to not be too invasive while still being able to gather both qualitative and quantitative data.

There were multiple objectives of this survey in order to maximize its utility for the research. Firstly, it aimed to gather preliminary information concerning conservation, environment issues in the area, and the monkeys in general. The goal of this first part was to have a global understanding of the Punta Burica in order to better design the rest of the research. The second part of the survey was focusing on the different pattern of community organization in place in the region. This part of the survey was here to help design the participatory part of the research. And thirdly, the survey aimed to gather data on where to install new monkey bridges. We decided that it would be more relevant to gather information on the monkeys based on the inhabitant’s observations rather than our own. It was more cost effective, time effective and more realistic, considering our low number of researchers, to opt for a strategy based on the people who have the most knowledge of the area.

Considering the little time we had to conduct the survey, we combined three sampling strategies to maximize the number of participants and the relevance of the answers. First, we decided to follow the rules of convenience sampling. We would interview anyone we would encounter walking about Punta Burica. The population of the area isn’t very dense so opting for this sampling strategy and staying in and around the main communities really helped us survey a significant amount of inhabitants. Secondly, following the first sampling strategy we decided to conduct snowball sampling. We would ask every participant at the end of the survey if they knew anyone else that could be interested in participating in the survey as well. And finally, we had decided to add a purposive sampling strategy in order to maximize the relevance of the data gathered. Indeed, we decided to interview both the bus drivers and SENAFRONT members, as we figured they were going back and forth along the highway multiple times a day and therefore were more likely to have information on the monkeys, their presence near the road, and their use of the bio-corridors. We had time to interview a decent amount of bus drivers, but the research was cut before having the time to interview enough SENAFRONT officers for their part of the result to be significant.

Below is the complete survey conducted during internship as well as its introduction designed to fulfill the ethical requirement of interviewing individuals.

Hola, somos estudiantes trabajando con la organización Proyecto Primates. Está organización lucha para la conservación de los monos de la península Burica. Estamos realizando entrevistas con los habitantes de la península para contribuir con el fin de esta organización. La información sería igualmente utilizada en el proyecto de investigación para nuestra universidad. El objetivo de esta entrevista es saber cómo los habitantes ven la conservación de los monos, como se organizan y donde es necesario construir puentes para los monos. Por esas razones quisiéramos saber si podemos entrevistarlo, la entrevista duraría entre 5 y 15 minutos pero usted podría parar la entrevista en cualquier momento o decidir de no responder a cualquier pregunta.

- Vive en la costa?

- Hace cuanto tiempo que vive aquí?

- Como se llama su comunidad?

- Sabe que tipo de mono hay en la región?

- A usted le importa la conservación de los monos?

- Le parece que la gente le protegen?

- Sabe qué peligro tiene los monos?

- Sabe cómo ayudar a los monos?

- Ha visto monos usar los puentes?

- Donde?

- Cuál tipo de mono?

- Ha visto monos cruzar por la carretera?

- Donde?

- Cuál tipo de mono?

- Ha visto monos atropellados?

- Donde?

- Cuál tipo de mono?

- Usted cree que es necesario construir más puente para los monos?

- Donde?

- Participa a una organización?

- Participó a una organización?

- Se puede ser como

- club de padre familia

- junto de agua

- ambiental

- pecadores

- ganadores

- agricoles

- iglesia (cuál tipo)

- fútbol

- Le interesa participar a alguna organización de la comunidad, una que no existe ya pero puede tratar de temas como el ambiente o la protection de los monos?

- Cual es su nombre?

- Cual es su Edad?

- Que haces en la vida? Que es su trabajo?

- Tiene un número de teléfono?

Luckily, we had time to conduct this survey during the two first weeks of internship. Moreover, we registered the coordinates of any data giving us locations to be able to implement them on the map.

We were also planning to gather information and data on the monkey populations based on the findings of previous studies from our supervisors, the types of terrain, the presence of living fences or the presence of some of the preferred fruit trees by the monkeys like the Espavé, the Caimito and the Higo. Sadly, we did not have the opportunity to collect all this additional data to perfect the results of our map.

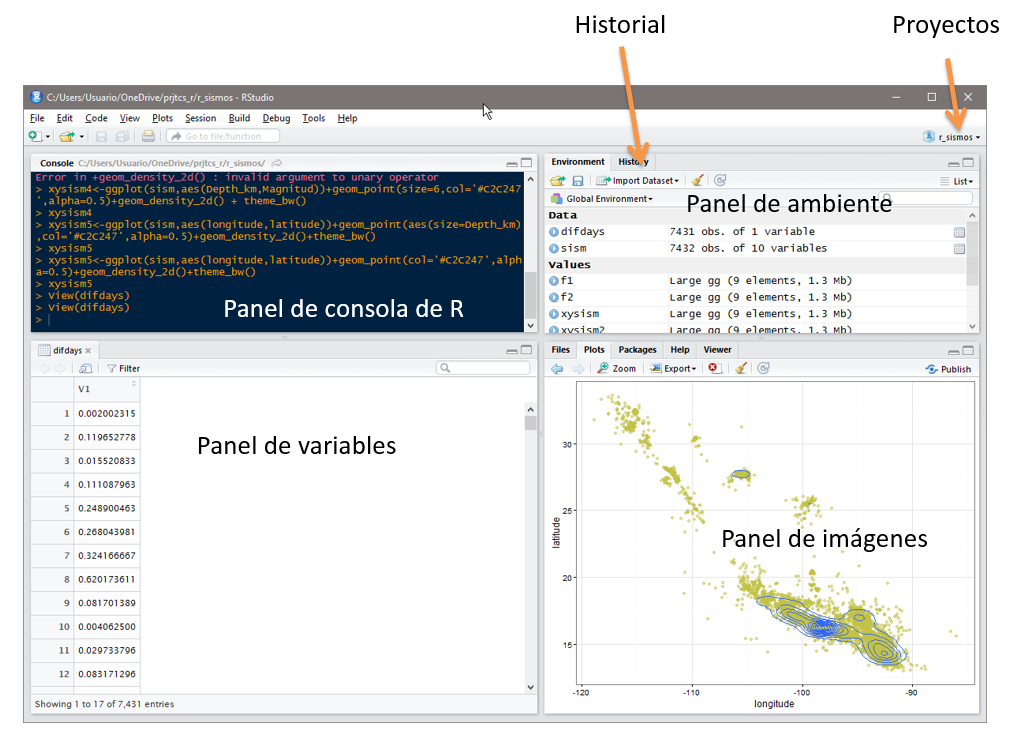

However, the map was done on GIS, a system allowing us to create maps using external data and satellites images. We were therefore able to add different types of land cover to the map based on satellite images like forest cover, pasture, and urban areas.

The sustainable monitoring network

The second goal of the project is to develop a sustainable monitoring network; it aims to have a permanent flow of information crucial for the conservation of the monkeys and its habitats. More precisely the objectives would be to encourage members of the community to be engaged in the preservation of the biodiversity of the area by giving them a role in monitoring the population of monkeys.

This part of the research project was the most affected by the drastic change of situation and therefore had to go through severe changes. The paper will firstly state what was originally planned in the methodology and then it will present the changes forced on the design.

- The original design

A community-based participatory research was selected to fulfill the requirement of a sustainable monitoring network and to analyse its functionality and its benefits. The goal would be to develop a communication platform used to share any useful information on the various monkey populations. Instead of creating an entire platform, we thought it would be relevant to use an already existing one, Whatsapp. It is an encrypted messaging app which can be used to send messages, photos, videos, audio recordings and locations. We chose this particular mobile application for its practicality but also because based on our observations it seems to be the most used communication platform in the country and in the area. Furthermore, using this application could give more freedom and thus a broader spectrum in the information received. The plan would be to create group chats in which we can add the willing participants for them to send any information on the monkeys that they might find appropriate to help. This strategy could be helpful in creating a large data set, unifying various data from different sources. It would be a means for the members of the community to participate in protecting the biodiversity that surrounds them. To maximize the data, it is important to set broad overarching guidelines so that it could encompass any information participants have, for example if there are monkeys seen crossing a bridge, or if they have a video of a troop of howler monkeys by the road.

The most crucial part of the project would be to achieve a high participation rate, as this participatory research design relies on the willingness of the population to participate. Furthermore, for the research to be more complete and more accurate, it would be essential to gather participants from different social, generational and geographical parts of the communities. To reach this goal multiple participants recruitment strategies will be combined. The first one is to contact every member who said yes when asked if they were willing to participate in a communal organization around themes like the protection of monkeys (Fig. 6). We would send them a message presenting the project and asking if they would be inclined to participate. The second strategy would be to put up posters (Fig. 3) in key places determined by the preliminary research including churches, the football club, schools, and bus stations. We would have also asked people directly if they were willing to participate, we were expecting to spend a good amount of time in the community which would have allowed us to develop this strategy. Finally, we would have used the snowball method once again and ask already participating members if they knew anyone else who might be interested in joining the monitoring network.

Combining all these strategies will increase inclusivity but there is one part of the population that this project can’t reach: the individuals without a phone. To try to counter this problem, we will ask the participants with smartphones and internet access to act as ambassadors, meaning they could share the information collected by other members of the community.

- Modification made due to Covid-19 crisis.

Due to our abrupt departure from Panama before finishing the internship, most of the design and the decision for this project had to be revised. The new strategy adopted is to develop a template of the sustainable monitoring network. We would create a guide on how to develop this project which could be helpful for our host organization to implement this project in the future. It consists of the steps that we think should be taken in order to establish the base of a monitoring network in the Burica Peninsula. Then because it was not possible to produce any tangible results to analyze, we will conduct a literature review combined with observations on the field and expected results.

We certify that this research has been conducted following the Code of Ethics of Mcgill University and that we have completed the TCPS 2: CORE.

Results

Map and Bridges

This map was created in the software ArcGIS (Fig. 1a). The map covers most of the area of the Burica Peninsula with the primary focus being the Carretera PTP-Limones. On the map are many important elements of the area. To start, there is a layer across the entire area that denotes the use of the land through color coordination (as described in the legend, Fig. 1b). Next, we added a green pin for each coordinate at which a temporary bridge already exists. Then coordinates were indicated by blue shapes depending on their relevance. To begin, blue star shapes were added to represent the locations that we believe a new bridge would be most beneficial. The blue circular symbol is used to signify other potential bridge locations based on tree positioning or suggestions from inhabitants of the area. The blue square shape denotes a location that could be useful for a bridge, however this location was found through aerial photographs rather than direct observation or recommendations from locals. And finally, a blue diamond was added for a location at which we observed monkeys (Mono Aullador) along the highway with our own eyes.

The information for this map came from a few different sources. Each coordinate was recorded on location during a walk along the length of the carretera. This was accomplished using the maps application on our cell phones and recording the coordinates as we got to the location of interest, along with notes about the location. These locations of interest were found through conversations with residents of the area, or through direct observation of monkeys or locations where a bridge seemed easiest to implement and most beneficial. Once all of this information had been gathered it was collected into the map where it could be presented in an organized fashion.

Included in our discussions with locals, we also learned about the use of the existing bridges. Through these conversations we found that the further south we went down the peninsula the more use the bridges saw. To elaborate, the first bridge between PTP and Las Mellizas had the least observed use and the southernmost bridge outside of Limones had the most use, with a gradient of usage sightings between. This could be due to many potential factors that we will discuss later in this paper. We also analyzed the patterns of monkey populations and bridge use. To this end, we looked at which monkeys were most often seen crossing the bridges and which monkeys were most often sighted crossing on the road. Our findings (displayed graphically in Fig. 2) show us that Mono Aullador are seen far more often than the two other species of monkeys in the area, both on the ground and on the bridges. As well, it seems the Mono Tití populations are making good use of the bridges as there have been almost twice as many sightings of Tití on a bridge compared to crossing the highway on the ground. Mono Cariblanco appear to be scarce in the region compared to the other two species but of the few recorded sightings about half were using the bridges.

Template for the monitoring network

- Elect a number devoted to the purpose of the monitoring network with Whatsapp.

- Create the group chats.

- Determine the administrators of the group chats who will have the power to add and remove numbers in the chat.

- Put up the posters (Figure 3) in the predetermined key places (Churches, Football club, restaurant, bus stops).

- When someone contacts the number wanting to participate, this standardized message is sent to them.

This same message can also be sent to individuals who have shown an interest to participate and have shared their number:

Hola, muchas gracias por escribirnos. (if they have contacted the number themselves)

Estamos creando unos grupos de chat para reunir información acerca de los monos en la Península Burica. El objetivo de este grupo es de colectar datos sobre de los monos para ayudar a protegerlos.

¿Sabía usted qué hay monos Concon, Cariblanca y Titi cerca de donde vive? Nuestra organización “Proyecto Primates” está trabajando para protegerlos a ellos y a su hábitat. ¡Pero necesitamos su ayuda! ¿Podría usted mandarnos un mensaje cuando vea algunos monos? y si es posible, decirnos cuántos eran, qué tipo de mono eran, donde estaban y cuando los vio. De igual manera si tienen fotos o videos nos lo puede enviar. Cualquier información sobre los monos puede ser útil.

Le pedimos encarecidamente no mandar mensajes inapropiados, si llegará a ocurrir nos reservamos el derecho de eliminar al que no respete las reglas.

Si usted quiere participar mándenos un mensaje con su respuesta, su nombre y donde vive y nosotros procederemos a agregarle a un grupo de chat en WhatsApp con otros participantes. De igual manera si conoce alguna persona que podría estar interesada en participar puede darle ese número.

Si tiene alguna pregunta no dude en preguntarnos. ¡Espero con interés poder trabajar con usted! (monkey Emoji)

- After that, add them to a group chat depending on where they live.

- Then you collect whatever information sent, photos can be used for the web sites, data can be added to the excel sheet we produce for the survey or to any other study done by Proyecto Primates Panamá.

- If there are any other specific studies requiring the ambassadors help you can send a message to the chats to see who is willing to help and send new guidelines.

- The group chat can also be used to send key information to participants regarding the primates and their habitat.

- Can be used to organize meetings or activities for informing the participants of the cause and push the organization of this community-based conservation further.

Following these steps should lead to a correct realization of a sustainable community-based monitoring network. This new tool could help gathering data but could also be useful to start new projects with the community and can be seen as a base for a future more complete organization of the community to better integrate conservation in the area.

The first question posed by participatory research projects is “will participation be high enough to have any significant results?”. If no one wants to participate this communication platform has no utility and all the effort put into this new incentive to protect the environment would be wasted. However, even if this project is very unlikely to have any negative impact on the communities because it is not invasive, for this project to have any ethical value, participation cannot be forced and the will to participate should come directly from the member of the community. Nonetheless, based on the preliminary survey we can expect participation rate to be significant enough. Indeed, we can see in Figure 4 that a very significant majority of individuals surveyed knew all three species of monkey present in the area. This proves that the inhabitants of the Burica Peninsula are aware that they share their lands with the emblematic animals. Furthermore, as we can see in Figure 5, when asked about whether or not conservation of the primates is a subject that matters to them, 40 out of 43 of the answers are positives. Thus, if people care about this theme we can anticipate that a majority would be inclined to participate. Finally, as we can see in Figure 6, when asked if they would be willing to join a communal organization concerning the environment and the protection of the monkey a significant part of the population surveyed answered yes. It is likely that not every person who seemed interested in participating will actually participate, but the numbers found in the preliminary research are encouraging.

Another parameter of this project that could be analysed is the content of the information collected. We could have expected to receive much information, for example whether or not monkeys are using the bridges, if a monkey is seen crossing the street on the ground, if the to-be-installed permanent bio-corridors are more used than the temporary ones, or if a monkey has been run-over. Based on the preliminary survey we expect participants to tell us exactly which species of monkey it was. We also expect the participants to use the tools given by Whatsapp and send any picture or videos taken of the monkey with their locations which would be incredibly helpful in the identification and the monitoring of the populations. Any of this information could be later used in different studies or projects conducted by our supervisors at Proyecto Primates Panama.

Literature Review

Finally, one of the most interesting parts when conducting a participatory research is to witness the benefits gained by both the researchers and the participants. Since we will not be able to observe such results, we conducted a small literature review showing the impact a well conducted community-based monitoring project can have. In his essay Rethinking Community-Based Conservation, Berkes states that “Community‐based conservation is based on the idea that if conservation and development could be simultaneously achieved, then the interests of both could be served” (Berkes, 2004). Later on, he will affirm that a system view is needed to properly achieve conservation of an area and therefore humans should be considered to be part of the ecosystem (Berkes, 2004). He goes further in saying that to successfully protect an area, a participatory approach is key, and humans should not be seen merely as managers or stressors (Berkes, 2004). Indeed, in the Burica Peninsula we have observed that the main problem for the monkeys’ preservation was human-induced habitat fragmentation including cattle ranching and the construction of a new road. But in order to implement functioning conservation systems in the peninsula, humans need to be considered in the equation as part of the system. The monkeys and all the biotic and abiotic components of the Burica Peninsula are sharing the same land and the same resources and should therefore be considered as such. In that sense, conservation lenses should be shifted from conserving a pristine nature point of view to a sustainable conservation point of view that could allow humans to benefit from their land without damaging it (Murphree, 2009). Keeping this in mind, a first step in reaching this ideal would be to attain conservation of the land through the empowerment of the inhabitants of the area (Murphree, 2009). In this case it could be achieved by implementing the monitoring network which can be seen as a way to start a discussion with the members of the communities in order to properly achieve a common goal. Furthermore, an argument that can’t be denied is that participatory monitoring is a cost-effective way of gathering more accurate data because it relies on the community knowledge and perception (Berkes, 2004; Danielsen et al, 2007). More generally, a sustainable monitoring network can bring capacity building and environmental education to participants (Şekercioğlu, 2012). It can in the long-term help in reducing the impacts of global change on biodiversity and the land (Şekercioğlu, 2012).

Discussion/Conclusions

Due to our untimely and unfortunate departure from Panama, this project had to be rather severely altered. However, we were lucky enough to have sufficient data to draw some relevant conclusions. First, we will touch on factors that could have affected the results of our surveys. Earlier it was mentioned that the bridges appeared to have more use further south on the peninsula. This result could be a factual representation of the distribution of the monkey populations, but this could also be biased due to a few different factors. The first of these potentially confounding variables is the number of people interviewed per area as we had far more interviews from the Limones area (very southern along the carretera) than from the more northern regions. As well, the bridges near Limones have people and homes very close to them which might make it easier for sightings to occur, whereas some of the other bridges are slightly more distant from observant eyes. Another factor that could have influenced our survey results is the people themselves. While there is no reason to distrust the answers given to us by the inhabitants of the area, it is always possible that people gave us answers that they thought we wanted to hear, rather than their own truths.

In the results section of the paper the map was briefly discussed. Here we will elaborate on the positions chosen on the map (Figure 1a). First, the blue stars that represent our recommendations for the locations of new bridges. The first of these (closer to the top of the map) is above the home of a very helpful family that is surrounded by trees. According to this family, they have seen monkeys cross in front of their home many times. The second star (at the bottom of the map) is on the road that runs above Limones, at a location chosen due to multiple accounts of monkeys witnessed crossing there, as well two conveniently placed trees that could make for an easy bridge implementation. As well, we have a firsthand account from a Limones local saying that they had witnessed a Mono Tití hit by a car on the road at which we want to implement this bridge and we have the hope that the addition of a bridge here will prevent a repeat of this event. Next, we will discuss the placement of the circular symbols that represent other possible bridge locations. The two placed at the topmost position of the map are placed on Puente Manzanillo No.1 and No. 2. This is because we had multiple accounts from locals of the Las Mellizas region stating that there had been many monkeys crossing on the road between these two roads. Heading south, the next circle symbol represents a spot along the highway at which there are trees close together across the highway allowing for easy bridge implementation. Unfortunately, this spot also happens to be right in front of an oil palm plantation which is not ideal for the monkeys and is not a permanent forest. Further south still, the next symbol of this kind is located at the intersection that leads down to Caña Blanca. This location was chosen because many Caña Blanca inhabitants stated that they have seen monkeys in this region and therefore we thought a bridge at this location could be beneficial. The final circular symbol is located at some farmlands above which there are a few trees that stretch close together over the highway. The trees allow for easy implementation but because of the farmland there is not much forest for the monkeys to inhabit on either side of the area. Next, the square-shaped symbol at roughly the middle of the map is representing a location at which a bridge could be beneficial but unfortunately was not scouted in person. Instead, the location was discovered through the aerial photographs used to create the map which revealed that there is forest on both the east and west side of the highway at this position, suggesting a fractured habitat. Finally, the diamond shape at the bottom of the map is representing a location at which we directly saw monkeys along the highway. The howler monkeys here were a rather large group and they were all eating in two trees along the road. This is to show a location where monkeys are at a potential threat of danger if they were to come down from the tree to cross the road without a bridge. As mentioned previously, the green pin symbols are the locations of the five pre-existing temporary bridges.

In conclusion, we managed to produce various results, from which we were able to draw multiple outcomes. First, our findings include a map which indicates where new bridges should be built to allow monkeys to cross the highway. We cross analysed multiple sets of data to find the locations that would have the most impact on the preservation of the monkey populations. With the first part of the research we have shown, as thousands of academics before us, the importance of Bio-corridors to combat the problems caused by habitat fragmentation. Secondly, we have produced a template for a sustainable monitoring network based on observations, preliminary research and a literature review. Doing so, we found that however arduous it can be to develop a useful participatory monitoring network, it is crucial for the good development of any conservation project directly or indirectly involving humans. To summarize, this project has shown us the complications that any conservation initiative entails. We have seen both the negative and the positive impact imposed by human presence in key areas for global biodiversity and discovered that development and conservation can and should go hand in hand. Furthermore, this research was built on the willingness to participate and the knowledge of the inhabitants of the Burica Peninsula. This concurs with modern views of conservation based on communities. It is a position we were hoping to investigate with the participatory monitoring network, however it has already been verified when developing the map. Indeed, the vast majority of the data used came from the knowledge and observations of locals.

Our host institution Proyecto Primates Panamá is an inspiring model in combining scientific knowledge and social development. The members of this organization understand the importance of the community component in the field of conservation and work tirelessly to reach the common goal of a better, sustainable environment for the entire peninsula. Even if our work was far from being finished in the short time that we had in Panama, we hope we have helped them by bringing valuable new information and a useful tool for future projects. Not everything was brought to completion, but we believe that the work done will be fruitful to continue new projects of conservation in the area. We trust that the map will be pivotal for the actual building project of new permanent bridges. We also expect the template to be a suitable tool for a considerable number of scientific and social projects. Maybe the impact we had will be small, but we sincerely hope that what we achieved will help the organization, the monkeys, the inhabitants of the peninsula, and the entire ecosystem of Punta Burica.

References

- Berkes, F. (2004). Rethinking Community-Based Conservation. Conservation Biology, 18(3), 621–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x

- Boinski, S., Jack, K., Lamarsh, C., & Coltrane, J. A. (1998). Squirrel monkeys in Costa Rica: drifting to extinction. Oryx, 32(1), 45–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3008.1998.00017.x

- Cuaron, A. D. (2000). A Global Perspective on Habitat Disturbance and Tropical Rainforest Mammals. In Conservation Biology, 14(6), 1574–1579. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.01464.x

- Danielsen, F., Mendoza, M. M., Tagtag, A., Alviola, P. A., Balete, D. S., Jensen, A. E., … Poulsen, M. K. (2007). Increasing Conservation Management Action by Involving Local People in Natural Resource Monitoring. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(7), 566–570. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[566:icmabi]2.0.co;2

- Dobson, A. et al. (1999). Corridors: Reconnecting fragmented landscapes. In Continental conservation: scientific foundations of regional reserve networks (pp. 129–170). Washinton, DC: Island Press.

- Haddad, N. M., Brudvig, L. A., Clobert, J., Davies, K. F., Gonzalez, A., Holt, R. D., … & Cook, W. M. (2015). Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science advances, 1(2), e1500052.

- Murphree, M. W. (2009). The strategic pillars of communal natural resource management: benefit, empowerment and conservation. Natural Resource Management and Local Development Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation, 15–26. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0174-8_2

- Proyecto Primates Panamá. 2019. Una iniciativa de Monitoreo, Conservación y Educación ambiental. Publicación independiente. 36 páginas. ISBN: 978-9962-13-072-7

- Şekercioğlu, Ç. H. (2012). Promoting community-based bird monitoring in the tropics: Conservation, research, environmental education, capacity-building, and local incomes. Biological Conservation, 151(1), 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.024

- Silliman, B. R., & Bertness, M. D. (2002). A trophic cascade regulates salt marsh primary production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(16), 10500–10505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162366599

- Tigas, L. A., Vuren, D. H. V., & Sauvajot, R. M. (2002). Behavioral responses of bobcats and coyotes to habitat fragmentation and corridors in an urban environment. Biological Conservation, 108(3), 299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3207(02)00120-9